It’s been 130 years since the invention of cinema. No better way to celebrate the art of motion and emotion than paying homage to the Lumière brothers (their surname means “light”), who offered a new way of seeing that continues to illuminate the world of cinema as well as modern-day travelers.

One cool day in Lyon, I found myself ambling along the city’s 8th arrondissement. A residential working-class neighborhood and once a creative hub to two of France’s revered figures. If Prometheus brought fire to mankind, the siblings were to become the stewards of light to the world of cinema and, in the end, gave cinema to the world.

Such a curious thing to be standing at 1 Place Victor Hugo, the same street where Auguste and Louis Lumière lived while imagining the world as they once saw it.

Long before travelers like myself flew over continents, zipped across one vast ocean to the next with smart camera phones and passports riddled with border stickers and stamps, it was these two quiet sons of a photographic entrepreneur who set something in motion: the idea that the world could be documented as it unfolded, with all its wonder and imperfection.

I have visited Lyon in the past. This time, I found myself pulling the end of an invisible thread that entwined the present to the days of the Lumière brothers for a fleeting glance of a world behind their lens.

Every crank of the cinématographe’s rotating shutter had serendipitously documented travel. It wasn’t just a novelty but also an invitation to see places, to connect, and to wander.

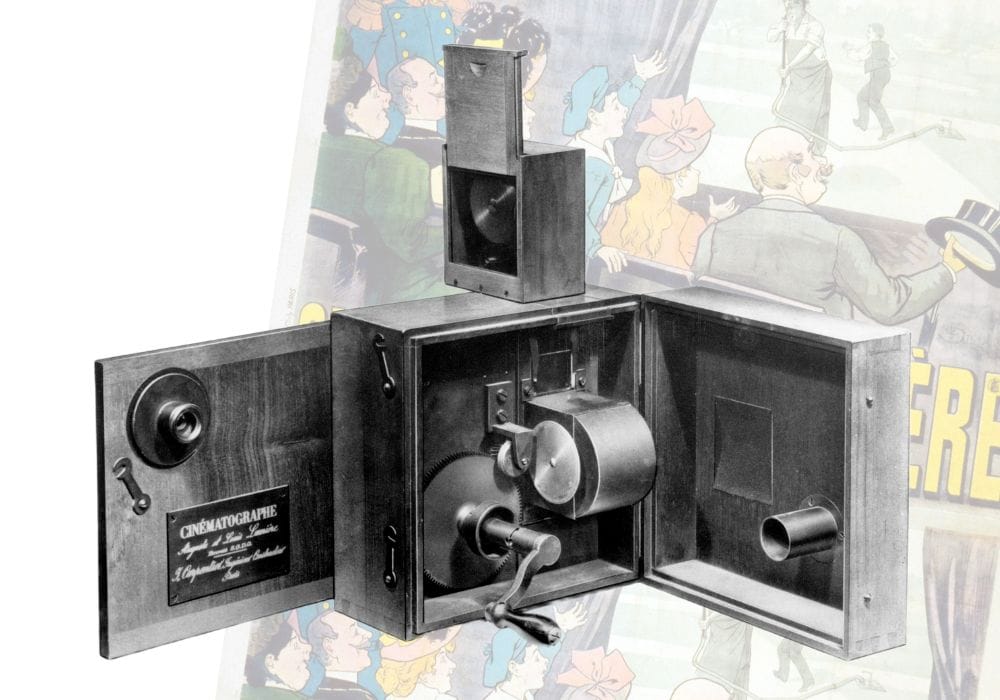

Behind the lens and inside the Lumiere Residence, now turned museum in Lyon. (1) An early projector on display. (2) The iconic portrait of Auguste and Louis, known as the Lumière Brothers worldwide. (3) A photo of Charles Antoine Lumière, the father of two of France’s revered siblings. (4) One of the bedrooms in the former Lumière Residence is on display in the museum. All photos by the Institut Lumière. Videos by the author.

Picture Lyon in the mid-19th century. A time when the third-largest city in France hummed the tunes of the industrial revolution. Between its busy, tangled lanes and riverbanks came forth a booming commerce and restless energy, along with a lucrative silk trade that powered the city’s engines of ambition, ultimately cementing Lyon’s place in history. Early photographic technology was one of the many innovative offshoots of that period.

From an early age the brothers were immersed in the language of light and chemistry. Charles Antoine Lumière, who runs a photographic portrait studio, sparked his sons’ interest in the moving film after seeing Thomas Edison’s ‘peepshow’ in his Kinetoscope demonstration in Paris. To the young, sharp-eyed, and mechanically gifted Auguste and Louis, the possibilities were endless as they sketched their first rough ideas of projecting films onto a big screen.

Just as science shaped the siblings’ perspectives, Lyon played a crucial backdrop in elevating their art form. The city presented itself as an irresistible canvas where the quotidien—the clanging trams, the lively cafés, and the hidden courtyards, were stories waiting to be captured and told.

By 1895, the birth of the cinématographe ignited the fuse of filmmaking. The brothers’ breakthrough of a three-in-one apparatus that could record and project motion pictures and develop film had triumphed over other early camera inventions of that period. The ingenious design and portability made it possible to capture images with ease.

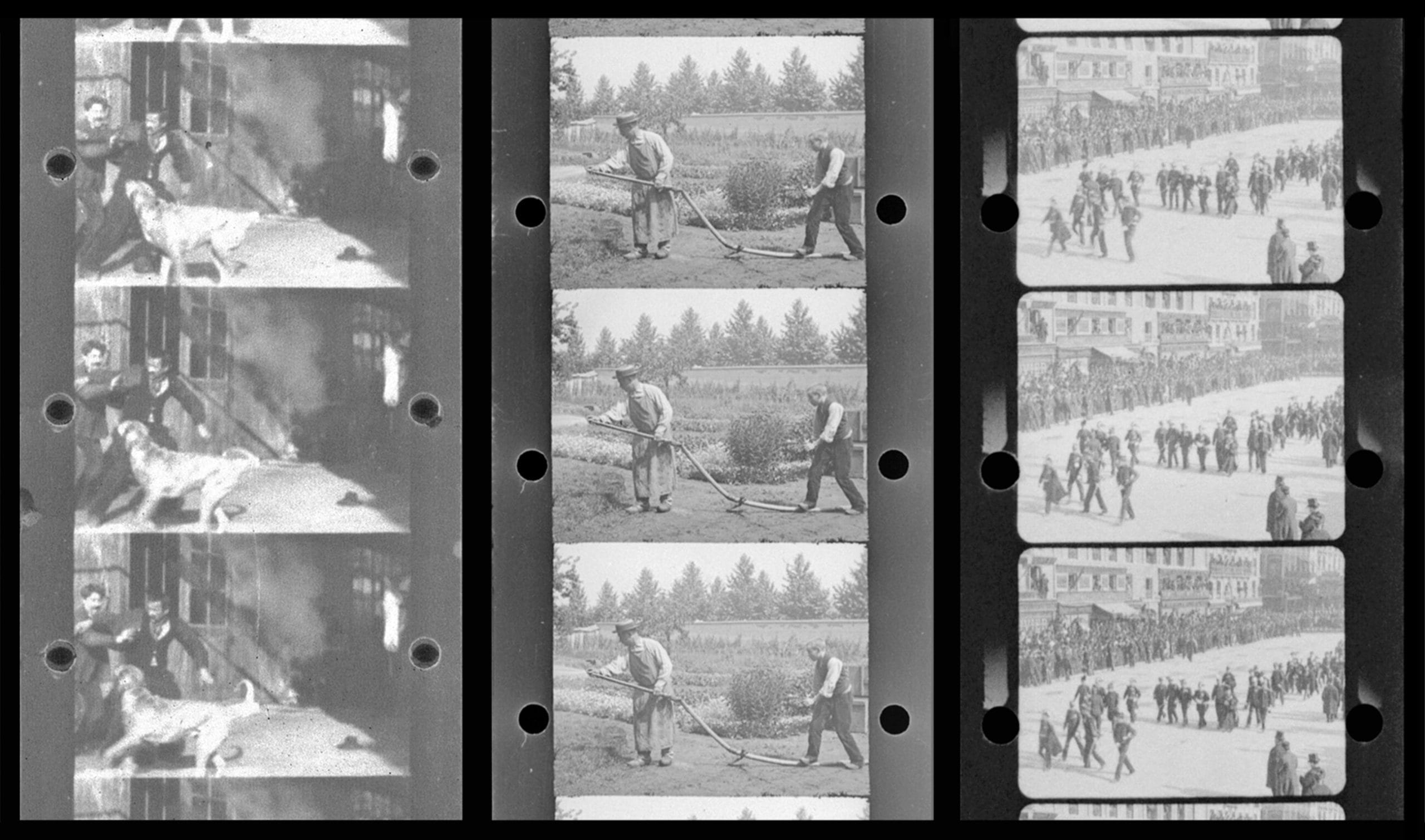

On a cold December in Paris of the same year, the Lumière brothers gave their first screening to a paying audience at Salon Indien du Grand Cafe, and ‘cinema’ was born (a term derived from the word cinématographe). The presentation consisted of ten short reels depicting a blacksmith at work, a gardener, a baby having breakfast, the sea, horse riders, and workers leaving the Lumière factory, just to name a few. Despite lasting an average of 40 seconds, each frame was seen as a small, fragile miracle. Movement, emotion, and life projected in light.

At the Café de la Paix, just a few steps from where the brothers first premiered, rumor has it that when the audience saw a locomotive train projected from a big screen hurtling straight towards them, they fled in a state of panic. Quite the effect, revealing the early impact and power of moving pictures.

The Lumières were not only engineers and inventors who were fond of innovation. They were also travelers and had an insatiable appetite to see the world beyond France. The brothers traveled and went on tour. They dispatched cinématographe operators to cities like London, New York, Buenos Aires, and some parts of Asia, which captured moments that defined humanity.

Their films from abroad showed bustling markets in Vietnam, camel trains in the Sahara, street life in Mexico, and video reels from Brussels to Bombay. For the first time, people from across the world saw a world entirely different from their own. How the other side lived, labored, and dreamed. Every crank of the cinématographe’s rotating shutter had serendipitously documented travel. It wasn’t just a novelty but also an invitation to see places, to connect, and to wander.

While getting up close with some of the Lumières memorabilia displayed in the museum and casting tender glances at their films, I noticed that in every snippet and frame was a telling narrative. There was no staged grandeur or choreographed spectacle. Instead it was straightforward appreciation in finding delight in the ordinary.

I sometimes wonder, as we frame yet another sunset for Instagram and Tiktok, what Auguste and Louis Lumière would think of us now. It often feels like a performance, a gallery curated for applause, a vicious cycle of vanity.

How many more times do we chase perfect angles, stage perfect lives, or pose with our perfectly fake smiles? We flood the internet beast with millions of images and reels every hour to please the algorithm and our pride. Somewhere between the shutter click and the scrolling thumb, I fear we’ve lost something that the brothers already understood.

In a time when travel can feel rushed and filtered beyond recognition, the Lumières remind me—perhaps remind all of us—that wonder lies in the unvarnished truth and the unrehearsed moments of the everyday.

As I exited the museum that houses the home of the Lumières, camera heavy around my neck, I thought about the old woman hanging laundry, the fleeting laughs of strangers, the boy chasing pigeons across a plaza, the ripple of a flag, the shimmer of sunrise on the Rhône, and the fading of sunset on the Saône the day before. My thoughts drifted, and as I continued to wonder, am I documenting the world or just collecting likes?

Maybe that’s the question for all of us travelers today: are we seeing the world…or are we too obsessed to be seen?

If the Lumière brothers were alive today, what would they think of our obsession with curated digital personas? Are we honoring their legacy of capturing life—or distorting it? Do we know how to be present in a moment without the need to capture it? Or has every experience become content? Love to hear from you in the comments below 😉

What a unique place to visit. Your video shows how well it’s been preserved too. It’s crazy to think how far we’ve come with editing and filters in a relatively short time. I agree with you – Auguste and Louis would probably be overwhelmed and shocked. It does make me remember why I take so many pictures – to find delight in the ordinary.

I would say we are curating life moments that were important to us and that we want to share, because they reveal parts of our personality. Just little moments, as you say. Could be a nice cup of coffee, a cosy spot, hidden garden or the floods of bikes in Amsterdam. I do agree with you that the typical Instagram content, however, is curated for the likes, to feed the narcissm and give a distorted picture of what the world really is.

Anyway, I was not aware that Lyon is a birthplace for the cinema nor have I have been familiar with the Lumiere brothers. It makes Lyon certainly very interesting to me and is exactly the kind of cultural character that I seek out on my travels. Once again, you have impressed me with your research and flawless poetic packaging.

Carolin | Solo Travel Story

I must visit the museum the next time I visit Lyon, a favourite city of mine. You sparked my memory of learning about the Lumière brothers back in university. How exciting it must have been for him to experiment with moving pictures! You pose an interesting question about our modern quest to record our lives. I know I record/photograph a lot of “life scenes’ that often don’t make it on my blog and socials, but those images/are the ones that often provoke the strongest personal memories and are the ones I pull out when sharing with friends. Once again, your beautiful writing will have me thinking about your ideas as I travel.

Did an inventor ever have a more apt name for the thing for which they are now known to have invented? What a magical find in Lyon, and such an interesting story of two brothers who made us see the world in new ways, who brought far off lands to those who hadn’t left their home. A thought provoking question about likes vs honoring the brothers, but either way, it’s showing the world and new places to people who have interest in seeing more of it

i’m a movie fan, but I am admittedly not drawn to foreign cinema and I do know a lot of the classic films are influenced by European cinema (especially films from Francis Ford Copolla and others). That being said, it was fascinating to learn about the Lumiere brothers, and their contribution of cinema through growing up in Lyon, France. I think one’s community is a big influence to the art that they create. Martin Scorcese tends to create films from a New York City perspective and it shows (especially Goodfellas!), and i’m sure their contribution fueled the passions of numerous film directors.